In astronomy, the average distance from the Earth to the Sun is approximately 108 times the diameter of the Sun. This ratio describes a stunning alignment, marking the Sun's diameter as a foundational unit in the measure of our orbital path. Similarly, the average distance from the Earth to the Moon is approximately 108 times the diameter of the Moon. And finally, the diameter of the Sun itself is roughly 108 times the diameter of the Earth.

These three simultaneous relationships whisper of a delicate, sublime balance in the heavens, suggesting that the number 108 is encoded within the very structure of our existence, a quiet harmony that underpins the chaos of everyday life.

In my family, we take the number 108 as a sign that good things are coming.

I still believe that’s true.

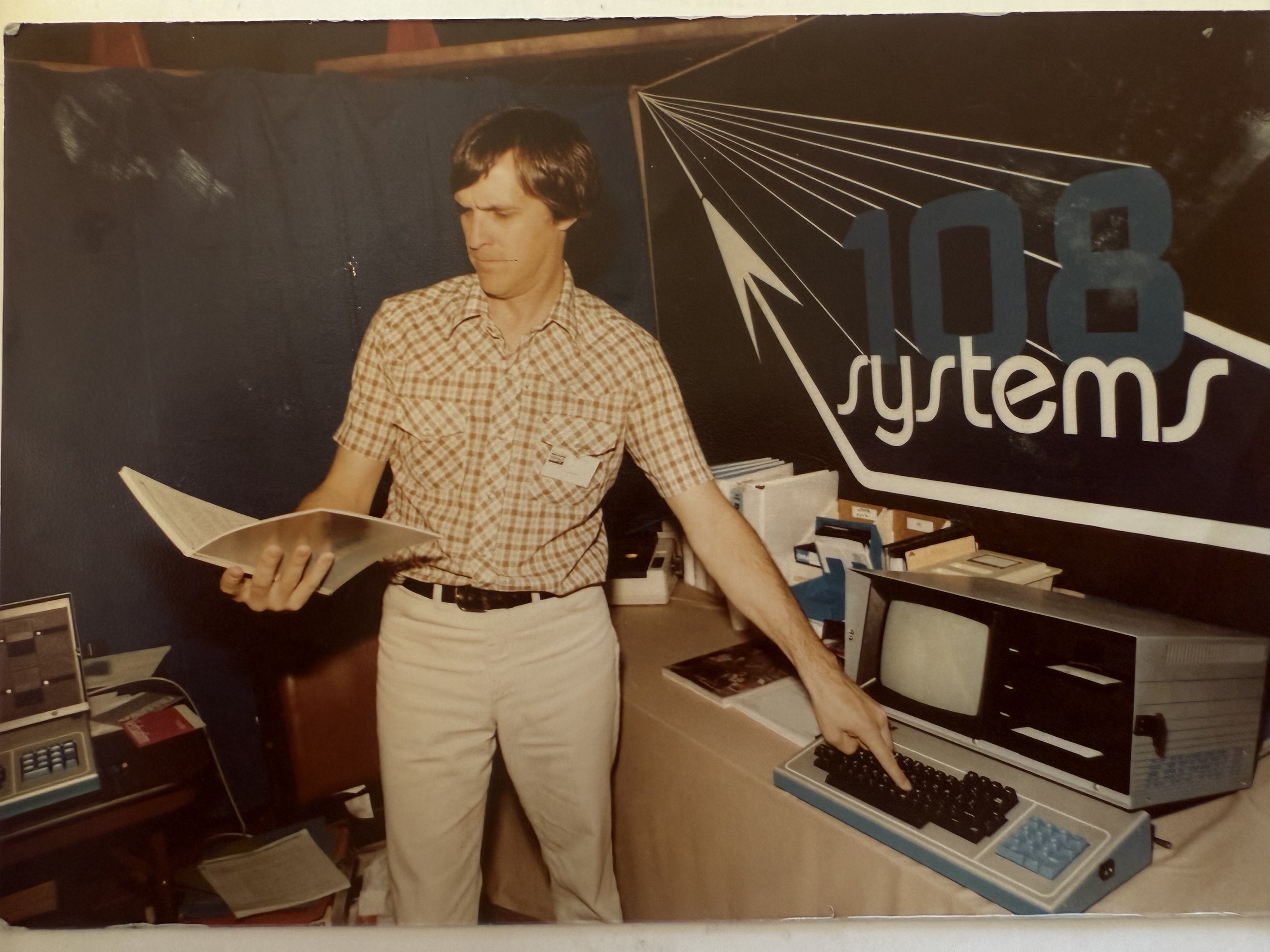

The name 108Labs is a tribute to my father, Ed Strickland, who started a personal computer company in the early 80’s called 108 Systems. He called it that as a tribute to his brother Dwight, with whom he shared a bond over the number 108.

I grew up surrounded by circuit boards and soldering metal in the era of the Apple II and the Z-80 SoftCard.

Innovation and entrepreneurship were a template he gave me, and 30 years later, when I wanted to apply my own skillset as a cell biologist to solve big problems, I rolled up my sleeves just as he had taught me to do.

This is for you, Dad.

I started 108Labs in 2013 with the assistance of my former spouse. The dream was to start a synthetic biology company on the back of my training in cell biology and his willingness to deal with all the red tape necessary to set up a lab. A group in the Netherlands had just produced a hamburger from cultured muscle cells. In the US, others were making leather from cultured skin cells. I was a mother with a painfully low milk supply, and I wanted to make milk with cultured mammary cells.

In an email to my best friend in October, 2013, I wrote:

I’m going to grow milk producing cells. Can you imagine If you could just culture cells in a dish and collect the milk? Aside from the obvious products based on cows milk, I envision doing this with human mammary cells so that women can feed their babies their own milk. […] Think of the impact in third-world countries where babies are malnourished and die of diarrhea all the time. I don’t think that milk produced this way will provide the same immune benefits as milk from the breast unless I can figure out how to include some immune cells in the culture, but if I can get the cells to make some milk, I think we’ll be in a position to attract a lot of attention and investment.

My husband and I put some of our personal finances toward the effort. He didn’t mind the administrative tasks that I find so burdensome, and he hustled to find lab space, set up vendor accounts, and register 108Labs as an LLC so that we could open a bank account and purchase materials for my experiments. I soon had a small space that was kitted out with a basic cell culture setup cobbled together from eBay, and I had guy on call at a local slaughter house who would give me a fresh cow udder for $20 cash.

One evening in 2014 after I was up and running in the lab, I wrote to another friend:

The cows in my experiment will be having a much worse day tomorrow than the cows over the fence at my neighbors farm. But hopefully whatever unlucky Bessie whose throat will be slit and whose sliced-off udder will be handed to me in a still-warm plastic bag and transported to 108 in a styrofoam cooler, as if for a BBQ, in just about 12 hours time, will end up being the great great great grandmother of a prolific lactating line of cells, whose multitudinous progeny will both multiply and divide in a precisely orchestrated sequence of events, the mixing and moving of chromosomes, the growing and shrinking of filaments, reaching then collapsing, reaching then grabbing, grabbing then pulling, EXPLODING, collapsing, and now the vesicles arrive, delivering tiny packets of milk, one by one, into the world. The same milk that will be chilled and beaten into ice cream to be placed on the tongues of my grand children, the sons and daughters of Levi or Violet. Here's to you then, Bessie. I do not look forward to meeting you in the morning.

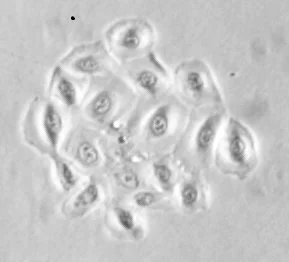

Indeed, I took the udder back to the lab, processed the tissue, and spent the next few weeks caring for the culture as the cells emerged.

Next to this picture I wrote, “these are the cells that I think are the milk makers.”

And that’s how it started.